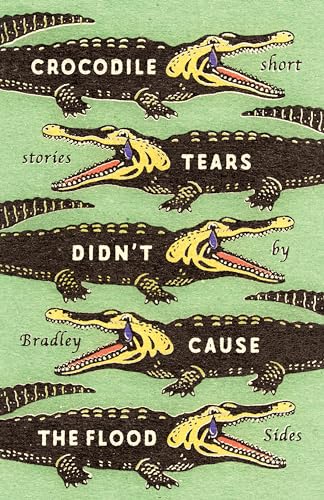

Ghosts, monsters, and falling celestial bodies mingle with the all-too-real in Bradley Sides’ new short story collection, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Start the Flood (Montag Press, 2024). In “Claire & Hank,” a boy grieves his father while struggling to care for an adopted Pteranodon. A haunted house shoulders the blame for a daughter’s disappearance in “There Goes Them Ghost Children,” while stars drop to earth after a flood in “Raising Again.” Fantastical creatures, some terrifying (pond monsters) and some funny (garlic-farming vampires), temper the grief, loss, and disaster present throughout the collection. Hope lightens the heaviest loads, as in the conclusion of “Raising Again,” in which Sides writes, “Although it was still dark and hard to see, the spreading light from above would guide their way.”

Ghosts, monsters, and falling celestial bodies mingle with the all-too-real in Bradley Sides’ new short story collection, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Start the Flood (Montag Press, 2024). In “Claire & Hank,” a boy grieves his father while struggling to care for an adopted Pteranodon. A haunted house shoulders the blame for a daughter’s disappearance in “There Goes Them Ghost Children,” while stars drop to earth after a flood in “Raising Again.” Fantastical creatures, some terrifying (pond monsters) and some funny (garlic-farming vampires), temper the grief, loss, and disaster present throughout the collection. Hope lightens the heaviest loads, as in the conclusion of “Raising Again,” in which Sides writes, “Although it was still dark and hard to see, the spreading light from above would guide their way.”

Sides’ first short story collection, Those Fantastic Lives: and Other Strange Stories, was published by Blacklight Press. His writing has appeared in The Chicago Review of Books, Electric Literature, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. Sides is a writing professor at Calhoun Community College and received an MFA from Queen’s University of Charlotte, where he was the fiction editor of Qu.

From his home in Huntsville, Alabama, Sides talked to me about the new collection, the agony of revision, and, of course, monsters.

INTERVIEWER

Your first short story collection, Those Fantastic Lives, came out in October 2021. That’s not very long ago, as these things go. Did you write new stories for this collection?

BRADLEY SIDES

When I finished Those Fantastic Lives, I had space between when the book was ready and when it came out. I was in an MFA program at the time, so it was a perfect opportunity to be churning out a story every month or so during those semesters. Within a two-year time period, I had most of the stories for Crocodile Tears Didn’t Start the Flood.

INTERVIEWER

That’s very impressive. How does this collection differ from your first?

SIDES

My first story collection has some experimentation in it, but in Crocodile Tears, I wanted to go all in and embrace that experimentation because I was having so much fun with it and it was working so well. Another difference is that this collection is very much about grief and loss. I used those themes as a way to put it together. Actually, two of the stories in this collection were included in the first draft of Those Fantastic Lives but they kept standing out to me as not belonging. I added them to this book and found they really fit with the themes.

INTERVIEWER

Now that you’re teaching full-time at the college level, when do you find time to write?

SIDES

A lot of creative energy goes into teaching writing, and I get a lot of fulfillment from my students and what they’re creating and helping them to build their stories. I’ve had a hard time writing in the past year because I moved and because of the state of the world. I haven’t found new space to write like I should. The last story I wrote for this collection was “2 Truths & A Lie About the Monsters Atop Our Hill,” and after that, I felt like I’d said what I wanted to say.

Currently, I’m building an outline for a novel. I’m the kind of writer who works on one thing at a time. I need to finish the story before I get to the next one. It’s hard for me to control the rhythms if I step away from it.

INTERVIEWER

While the collection deals with some heavy subjects – along with grief and loss, the apocalypse comes to mind – there’s a sense of play and nostalgia in many of the stories. One example is “To Take, To Leave,” which is written in the format of a Choose Your Own Adventure book. What inspired that choice?

SIDES

That story has a long history! Originally, I wrote a very short piece of flash about a mother figure who comes down from the sky during an apocalypse, but the story never worked. There was something about the end that wouldn’t come together. I took the idea and expanded it and, in that process, the world grew and the characters changed. After tinkering with it here and there, I finally realized that this story is really about choice. So, I took that choice and brought it literally to the page. I was experimenting when I had a moment where I thought, “Yes! This is what the story is supposed to have been all along.”

INTERVIEWER

A letter, a training manual, a transcript, and a standardized state test also serve as the forms for stories in this collection. Do you tend to start with a more traditional narrative and then alter it to fit an experimental form?

SIDES

Pretty much all of my stories go through a lot of revisions. It’s not uncommon for me to go through twelve to twenty versions before I get them where I want them to be. For the experimentation stories, they came naturally in a lot of ways. Covid was going on, the world was very dark and falling apart, and I needed a way to be excited to write. I needed to internally motivate myself to tell the stories. Because the forms were so entertaining, my outlook changed from “you have to write today,” to “you want to write today.”

My goal wasn’t, for example, to fit a story into the form of a state test in “Nancy R. Melson’s State ELA Exam: The Dead-Dead Monster.” That is a story about a person taking a test and it just so happens that the test form found its way into the story. I thought it added a nice layer. I hadn’t seen a ton of experimentation like that. I felt like I was creating something different, something unique.

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk about which story was the hardest to write from an emotional standpoint?

SIDES

If I had to narrow it down, I’d say “Festival of Kites.” As I was creating this world with these people who knew death was coming, I could see the image of people floating off into the sky like kites. The way death is approaching made it a heavy kind of story. Once I finished it, I had to step away for a while because while it was fantastical, it was really real to me. When it was done, I just had to sit with it. I spend a lot of time with endings, often going back and revisiting, but with that story, it had this song quality, an almost hum to it that I thought was necessary.

INTERVIEWER

In general, how do you know you’ve found a story’s ending?

SIDES

I read for emotional states. If the story doesn’t end with the right emotional feeling, then I haven’t delivered. Often, I’ll cut a page or a paragraph because I’ve given too much away. I’ll go back, cut, and give my reader a little bit of power back.

INTERVIEWER

I really enjoyed reading the names of your characters. One name that comes to mind is Peaches in “Peaches’ Menagerie.” She’s an older woman with the macabre skill of transforming sick babies into animals, yet she has this soft name. In the process of writing that piece, when did you name Peaches?

SIDES

From the beginning, Peaches was the name that came to me. Being from the South – and I’m in the Deep South – people have unique names that are not common throughout other parts of the country. Names are a way for me to bring “home” into my stories. Playful, less traditional names remind me of here, and that makes the characters, and their stories, more real.

INTERVIEWER

The Southern feelings came through in the characters, their manners of speaking, the settings, and the names, too, which hadn’t occurred to me until now.

SIDES

Yes. It would be difficult for me not to write with a rural setting, given where I’m from. I grew up on a cattle farm, which meant I spent a lot of time outside, under trees, with animals. Seeing the natural world, being in it, that was my childhood. I don’t feel like I’ll ever escape the home influence in my writing. Instead, I embrace it.

INTERVIEWER

When you’re writing a story, especially a speculative one, are you envisioning a place that exists?

SIDES

When I was growing up, we had this huge pond in our backyard. The entire landscape was very green, very alive, very bountiful. In a lot of my stories, that is the setting. “The Guide to King George” for example, has the pond, the tractor, the very rural environment. If you look at “Claire & Hank,” there’s the same thing, the pond, the animals outside. The farms I’ve seen my entire life show up in stories like “Dying at Allium Farm.” They are home to me.

INTERVIEWER

Humans transforming into creatures or objects comes up a lot in the collection, like in “The Browne Transcript,” where the main character insists his wife and kids have been turned into moths. What purpose does transformation serve in your work?

SIDES

I think it relates to escape. When I was writing the stories in this collection, it was a difficult time. People were trapped in different ways: by health, by isolation, by politics. There was a drive to escape. We were trying to escape the traps we were in, and I think that need to escape comes through in the stories.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about monsters. There are a lot of monsters in these stories, like the dragons in “2 Truths & A Lie About the Monsters Atop Our Hill” and the pond monster in “The Guide to King George.” When you’re describing monsters, how much do you leave to the reader’s imagination?

SIDES

When I’m reading, I like a lot of power. I lean that way in how I write, too. I try to give enough so the reader can sense the scope, and some of the physicality of the monster, but I don’t want to give too much away because I think there’s a lot of power in the fear and unknowing. What readers create in their own minds is much scarier than most writers can create on the page. That’s one of the appeals of writing a good monster: to wait, to wait, then see how the monster grows with the reader.

INTERVIEWER

Do you believe in ghosts?

SIDES

I don’t not believe in them.

INTERVIEWER

I would ask the same question about monsters, too, though it’s a bit harder.

SIDES

To me, monsters are very real. I think we see them all the time. They take many forms, but they’re very present in our world.

INTERVIEWER

In terms of length of story, there’s a variety here, from a couple of pages to over thirty. What’s your preferred length to write? To read.

SIDES

I’m most comfortable writing in the eight-to-twelve-page range. That length gives me space to do what I need to do without lingering. I’m not an overly descriptive writer, I don’t spend too much time with exposition. My stories tend to begin with conflict, and I try not to overstay.

I love flash. I love what it does. I love the language. The flash that I read has a lot of ambiguity. I’m drawn to reading flash because of what writers can do in such a short space. I love the mystery. It’s all about the mystery.

https://www.bradley-sides.com/

Interview Conducted by Joanna Theiss