Can a smile cast with sincerity be anything but good? That’s one of the many questions Charles Harper Webb poses in his novel, Ursula Lake.

Webb became an avid fly fisherman while attending the University of Washington. He has his three main characters in Ursula Lake share their connections to the university while on a fly fishing trip in the remote woods of British Columbia. Just as Webb earned a living as a rock guitarist in Seattle before moving to Los Angeles to further his music career, Scott, the novel’s most developed character, plays guitar in Seattle and mulls a move to Los Angeles during his trip.

But Webb remains foremost a poet, placing his characters in a setting where the subalpine lakes collect snowmelt and shift appearance based on perspective: gin-clear on the shore, blue-green from a ridge in the distance, darkening gray at dusk. Life thrives in these waters, fish and frogs spawn – feeding and mating, insects hatch, and black-flies bite. The ice has just melted in mid-May and the snowpack retreats further up the mountains into the thick firs and spruces.

The poet in Webb references other poets. He has Scott warming to his ex-best friend’s wife not long after meeting her. Webb takes the reader inside Scott’s inner consciousness:

Like Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” she was promiscuous with smiles.

How could that not be a good thing?

Far out on the darkening lake, the loon continued to lament. What had been a slight breeze was turning into a cold wind.

In Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” the Duke of Ferrara recounts the painting of his deceased wife. The Duke’s courtly manners and ambivalent phrasing mask a rising tension like a darkening lake obscures trouble below. Browning demonstrates how beauty can turn deadly in the way a slight breeze turns into a cold wind. The Duke’s resentment turns precisely around that spot of joy, that promiscuous smile. The Duchess flashes that smile to everyone and everything from the Duke’s favor, to sunsets, to a bowl of cherries, to riding a white mule.

The Duke cannot explicitly explain his irritation. He cannot explain how much his wife’s spot of joy enrages him, even perhaps to the point of murder. Instead, he represses his anger, preventing him from closure––he hasn’t moved on from his last Duchess though he’s leaving the painting to obtain a new one, a new Duchess. The spot of joy remains a reminder of the defeat of the Duke. He’s unable to share his wife’s enjoyment in life and sees himself as a failed husband. Some critics have drawn attention to the poem’s precise punctuation, the clipped asides, and the false exclamations to symbolize a fear of castration by the Duke, if not at least sexual jealousy.

Errol drives into the novel with a brand-new monster-size Ford pickup truck and parks it across three spaces at the town’s only restaurant. Playing the Duke, Errol explains his motivation for the trip:

“I work my balls off all year. Now we’re starting to catch fish . . .” He seemed incredulous. “You really want to leave?”

Claire stared at the metal boat-bottom. The last thing she wanted was to be the scaredy girl.

“If it means that much to you,” she said, “I’ll stay.”

Errol brightened instantly.

Errol, Claire’s husband, seems unable to enjoy those fifty-one other weeks of the year where he has achieved relative success in business and love, especially when contrasted to his now no longer ex-best friend Scott. Errol cannot find enjoyment in primeval forests or glacial lakes either. He only cares about catching fish. His indolent mood steadily rises as Scott (and then Claire) catches more fish than him.

In “My Last Duchess,” only the Duke speaks. The stand-in for his sexual rival, Fra Pandolf the painter, has expressed himself through his art, and his last Duchess, now deceased, expresses herself through that spot of joy and her countenance. The novel form allows the reader insight into the inner monologues of all three characters in this art-imitating-art love triangle. Throughout the seven days of the fishing trip, Webb takes the reader into the minds of Scott, Errol, and Claire, often switching perspectives in the middle of a sequence.

Errol, the jealous husband, remains repressed, teetering on the verge of humiliation, still unable to share in the joy of life. His anger towards Scott hasn’t subsided. Throughout the trip, the reader finds out why they split up and didn’t take steps to repair their relationship. Now Errol’s jealousy over Claire’s promiscuous smiles adds a new dimension. But Errol doesn’t have the Duke’s wealth and privilege. He married up in social station. So, can a poor theater major be doomed to the same repression as the pompous Duke?

Scott’s monologues are Hamletesque in their indecisiveness. Although this novel is billed as fast-paced, it takes time for Scott’s attraction toward Claire to build, just as no big trout has ever been caught immediately in a fishing story. Besides, Scott has other things on his mind. He’s up here by himself and except for a relatively new girlfriend, no one knows where he is. He’s thinking about moving to Los Angeles, following in Webb’s footsteps, but also thinking about law school, following his dad into the practice. He’s thinking about making a move with Claire, but he also believes it’s inappropriate to do to his best friend’s wife. His girlfriend back in the States gets less headspace.

Despite his thoughts, Scott takes decisive action from the novel’s opening. An hour outside of Vancouver, the end of civilization, he sees a doe on the side of the road hit by a monster truck. The doe still lives but is past the point of saving. Most people would keep driving, but Scott comforts the animal, anthropomorphizing:

He pictured himself standing like a deer in thick woods, smelling the pine, the damp, the tang of leaf-decay. The greenery around him swayed in a slight breeze. As if it were breathing. In his mind, he began to run. Still a man, but with the grace and power of a deer, he bounded up high hills, and down. Following trails that squeezed under gigantic trees and through tangles of briared brush, he ran with what felt like unlimited power and a sense that the deer had called him here for something special. Something grand.

Scott doesn’t see anything wrong. He doesn’t see the dead deer as a bad omen or that he might one day see a monster truck bearing down on his little blue Datsun in his rear-view mirror, finding the same fate as the doe. No, he’s called for something, but what?

Claire is five years older than the boys, while thirty-three doesn’t make her middle-aged; she sometimes feels old amongst the two boys as they fish and banter, occasionally tediously, like twelve-year-olds. She’s had other loves. Errol is not her first husband. With access to a trust fund, money is not an obstacle, so what is holding her back?

Whether because Webb has difficulty writing a mature female mind as intimately as he does the two boys or because he’s holding back to add surprise to the novel’s action, Claire remains the least developed of the three characters. But maybe the reader is too distracted by her charms to consider what if the Duchess was more like the Duke outside her portrait painted by a romantic.

Like these three, I spent a week in mid-May fishing with my college buddies in Canada back in the nineteen nineties, before smartphones. Departing from a small outpost town on the main highway, we followed local roads, which quickly turned to dirt and rock, ultimately leading to a small cabin overlooking a glaciated lake. During that week, we discovered that the first lake led to another lake and then another. These deep freshwater lakes were guarded by forests of Douglas firs, stands of spruces, and interloping birches. When the fish weren’t biting, we hiked in the uncharted woods. In thick brush with no one around, we discovered nameless mountains and cliffs along herd paths crossing dirt roads and streams. We climbed higher away from the lakes below. We split up sometimes too. We caught fish, released many of them, and ate a few––delicious.

I found myself returning to this spot while reading Ursula Lake. Heading out with the boys for the morning bite and again in the evening, looking for inlets and bays, remembering the way back, searching for new lakes, better fishing spots. Admittedly, I didn’t follow Webb’s many fishing tactics. Still, I know the weather changes quickly out on the lake. Capsizing into a recently thawed lake leads to hypothermia, and in survival mode, alliances change like the weather.

There’s a fourth person in “My Last Duchess,” the person the Duke is addressing. Browning gives little indication about the type of person the listener is, a man presumably. Why does the Duke feel comfortable showing this man his ex-wife’s portrait, which he usually keeps hidden behind a curtain? Is this man not a sexual rival? Is he more like the Duke in a sinister way? There’s a fourth person on the lake too, but how could he resemble any of the other three? Webb doesn’t share the fourth wheel’s thoughts after all.

Webb has built a superb list of publication credits as a short story writer. He repeats Checkov’s rule when the pistol goes off, the shotgun blasts and the hatchet finds blood. The same logic also applies to that creepster Claire blows off at the bar––and to the eighty-dollar sunglasses Scott needs to prevent headaches. So what else might follow the rule in Ursula Lake?

The smile she sent back made his breath feel jiggly. Then they were off, letting their lines out into water turning gray under the lowering sun.

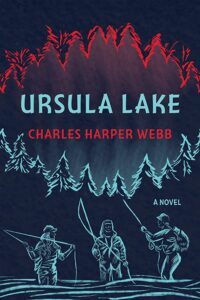

Charles Harper Webb

Publisher/Imprint: Red Hen Press

Pub date: May 17, 2022

Page count: 288pp

ISBN: 978-1-63628-021-9

Tagline: In the fast-paced, sexy, and very scary literary thriller Ursula Lake, a husband and wife trying to save their marriage and a rock musician trying to get his career back on track find big trouble, natural and possibly supernatural, in the spellbinding wilds of British Columbia.